From the 1970s onwards, the Netherlands played a prominent role in supporting struggles for women's rights around the world. Feminists, policymakers, academics and activists cooperated with women's movements in the Global South to advance women’s rights and gender equality. Yet this feminist engagement has been neglected in the historiography of development cooperation and the women's movement in the Netherlands.

Klik hier om dit artikel in het Nederlands te lezen.

‘What this cooperation between different actors has achieved throughout history has remained underexposed,’ says Ireen Dubel, who herself worked in Dutch and international development cooperation for more than 35 years. Her surprise at this omission was the starting point for an ambitious research project that began in 2017 and ultimately resulted in a richly varied book about fifty years of feminist solidarity: Dutch Transnational Feminist Solidarity Activism across North-South Divides.

“What this cooperation between different actors has achieved throughout history has remained underexposed.”

Underexposed in the history of development cooperation

Since the International Women's Year in 1975, the Netherlands has played a prominent role in supporting struggles for women's rights around the world. Dutch actors – from civil servants and NGOs to universities – contributed to policy, knowledge and international networks with the aim of strengthening the position of women in the Global South.

‘Our two gender equality ladies: Mrs. Thomas [right] and Mrs. Schoustra van Beukering [left]’, in BZ 6(5) (May 1979), the monthly journal for employees of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

‘Our two gender equality ladies: Mrs. Thomas [right] and Mrs. Schoustra van Beukering [left]’, in BZ 6(5) (May 1979), the monthly journal for employees of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

While searching through archives, the author came across pioneers such as Geertje (Thomas-)Lycklama, co-founder of the Vrouwenberaad, a network of women working in development agencies. ‘Lycklama personified one of the common threads of my research: the importance of collaboration between feminists from politics, government, academia and civil society.’

Partly on her initiative, a biography of Lycklama has been published in 2023, written by Johanneke Liemburg.

An archive full of stories

The book is not only a historical overview, but also a personal quest. What started as a project alongside a job, expanded into a full-time assignment from 2018 onwards.

The starting point was an extensive personal archive: “grey material, newspaper clippings, policy documents, travel reports, notebooks and correspondence”. That archive, built up since the 1970s, formed the backbone of the research.

With the help of a group of co-readers – ranging from academics to (former) civil servants and former colleagues – a research framework emerged. The conversations with key figures, including former minister for Development Cooperation Jan Pronk, were inspiring and a welcome break from the archival research.

Scholarly literature helped the author to deepen her analysis of the primary research sources. "The literature opened my eyes. Looking back, I was able to comprehend social and political developments, which was much more difficult when I was still in the thick of it. As journalist Geert Mak observed: 'It is rather complicated to write history while you are living in it. Good history writing needs time, sometimes decades, and when you are in the middle of it, you can make some observations, sometimes good observations, but often you cannot see what’s happening in the long term – you need distance for that.“ (F. Laczó in collaboration with K. Culver (2021) 'Geert Mak discusses with the historian Ferenc Laczó’, 1 November).

1975: a starting point for new international feminist solidarity

One of the first surprises to emerge from the research concerned the first UN World Conference on Women in Mexico City in 1975. For the Dutch government, a week of attention to women was more than enough, but it could not ignore its obligations to the UN, which had proclaimed 1975 as International Women’s Year. The feminist protest group Dolle Mina demonstrated against the official committee that the government had established to pay attention to International Women’s Year. The message was straightforward: International Women’s Year was ‘a little piece of cloth to stop the bleeding’ - ‘a mere eyewash’.

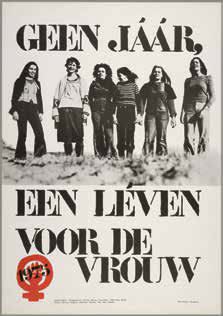

Dolle Mina poster 1975, ‘Not just a year, but a lifetime for women’

Dolle Mina poster 1975, ‘Not just a year, but a lifetime for women’

At the same time, there were major geopolitical tensions at the international and global levels. In Mexico City, Minister Jan Pronk, head of the Dutch delegation, advocated for the need for a new international economic order – a position that clashed with that of his political party colleague and Minister of Foreign Affairs, Max van der Stoel.

Even more remarkable: the Netherlands voted in favour of the final declaration despite the inclusion of the phrase ‘elimination of Zionism’ – a unique political position in Dutch UN history. ‘Looking back now, that position is not only unique, but surprising and astonishing,’ the author concludes.

Forms of solidarity: from abortion rights to anti-apartheid protests

The book provides insight into how feminist solidarity took shape in various forms: temporary, long-term, and some still relevant today.

Ireen Dubel describes the role of the women's group of the Anti-Apartheid Movement Netherlands (AABN), active from the late 1970s to the early 1990s. She also devotes considerable attention to the Dutch commitment to global access to safe and legal abortion – an issue that Dutch feminists have been campaigning for since the 1970s.

From left to right: ANC women Rose Motsepe, Shirley Mashiane and Bunie Matlanyane Sexwale, demonstration South African Women's Day, Amsterdam, 1986

From left to right: ANC women Rose Motsepe, Shirley Mashiane and Bunie Matlanyane Sexwale, demonstration South African Women's Day, Amsterdam, 1986

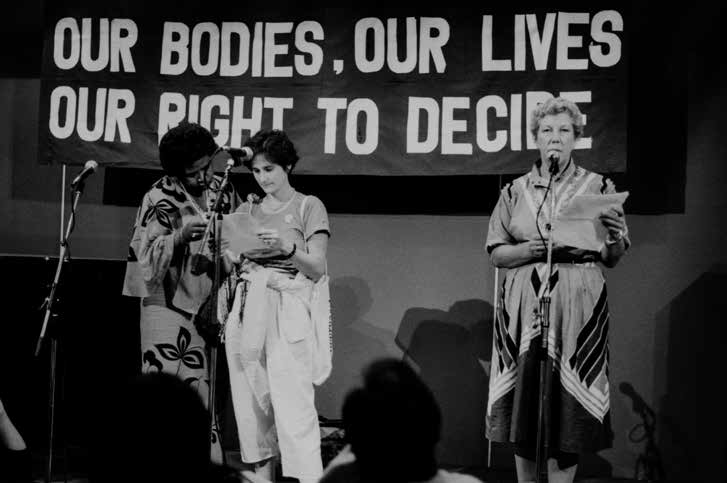

In 1984, Amsterdam hosted the Women's International Tribunal and Meeting on Reproductive Rights, organised by the abortion committee Wij Vrouwen Eisen (We Women Demand). For the first time, many women from the Global South also took part, extendingthe debate on women’s right to decide over her own body to include issues such as condemnation of abusive population control policies and the formalisation of the idea of women’s reproductive rights as the right to decide whether, when and how to have children – regardless of nationality, class, race, age, religion, disability, sexuality or marital status – in social, economic and political circumstances that enable such decisions.

Tribunal and Meeting on Reproductive Rights, Amsterdam, 1984.

Tribunal and Meeting on Reproductive Rights, Amsterdam, 1984.

“‘The meeting in Amsterdam was the starting point for the development of the international reproductive health and rights movement,’ according to the author.

Professionalisation of feminist engagement

Over the decades, the nature of international feminist solidarity changed drastically. Whereas in the 1970s activists took to the streets to demonstrate, the movement professionalised in the 1980s and 1990s.

Advocating for women's rights increasingly became part of policy processes, knowledge development and diplomacy. ‘Professional advocacy became more prominent,’ writes the author. ‘Direct, visible protests faded into the background.’

This professionalisation enabled long-term commitment, partly thanks to government funding. However, there was a downside as well: financial dependence on a government that increasingly focused on short-term policy outcomes and measurable results at the expense of tough long-term issues such as safeguarding women’s rights and advancing gender equality. Until early 2025, when the Schoof cabinet announced that women's rights would no longer be a priority in Dutch development cooperation policy, the Netherlands has been one of the world's leading funders of women's organisations worldwide.

The legacy of solidarity

Dutch Transnational Feminist Solidarity Activism across North-South Divides shows how feminist advocates repeatedly opened and created new ways forward despite political setbacks.

A striking example: Women on Waves

Since 2001, Women on Waves has been drawing global attention to the high maternal mortality and morbidity rates due to unsafe and illegal abortions, initially with the abortion ship and subsequently with drones and robots, safe abortion hotlines and online provision of the abortion pill.

Even before the abolition of the federal right to abortion in the United States in 2022, Women on Waves launched the Aid Access initiative, which provides the abortion pill in America. In the Netherlands, too, Women on Waves is committed to the legalisation of abortion and self-regulated medical abortion with the abortion pill.

Women on Waves’ commitment shows that feminist activism is able to reinvent itself.

‘What I want to show with this book,’ says Ireen Dubel, ‘is the importance of cooperation between different actors – from government, academia, politics and civil society – across national borders. Only in this way sustainable results can be achieved.’

“What I want to show with this book is the importance of cooperation between different actors – from government, academia, politics and civil society – across national borders.”

Looking to the future

Although there are no one-to-one lessons to be learned from the past, history does offer valuable insights. The book invites readers to reflect on those who came before them and know on whose shoulders they stand, and what made their efforts possible.

‘I hope that readers, especially advocates and policymakers, will take away the message that change is possible – even when the political tide is not in their favour.’

The author is currently working on her doctoral research at the University of Amsterdam, where she is investigating questions about transnational feminist solidarity, power dynamics and North-South relations. With her book, she hopes to bring a forgotten history to light – and inspire a new generation to continue the tradition of international solidarity.