What connects Rembrandt van Rijn and Amsterdam’s Royal Palace on Dam Square, the magnificent building that until 1806 functioned as city hall? Both are prime examples of the economic and cultural wealth of seventeenth-century Holland, the period often described as the ‘Dutch Golden Age’.

Klik hier om dit artikel in het Nederlands te lezen.

Rembrandt (1606, Leiden-1669, Amsterdam) came from Leiden to Amsterdam when he was about 25 years old. The large market of wealthy clients had drawn him to Amsterdam. His artistic breakthrough was in 1632, when he delivered the group portrait ‘The anatomical lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp'. The painting depicts a specific Amsterdam phenomenon, the typical urban organisation of trade, industry, and services in guilds. Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1593-1674) was appointed as public anatomist (praelector anatomiae) of the Amsterdam Guild of Surgeons. He would also become burgomaster of Amsterdam for four times, including during the years 1654 and 1656 when the new city hall in Amsterdam was completed. Rembrandt would become the painter to go to in the third and fourth decades of the seventeenth century.

Rembrandt (1632), The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp [Mauritshuis, Den Haag]

Rembrandt (1632), The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp [Mauritshuis, Den Haag]

Inside today’s Royal Palace, however, we find marble halls and corridors filled with art, but no Rembrandt! Why was the famous painter’s work turned down for inclusion in Amsterdam’s city hall? And which events nevertheless made the artist-entrepreneur’s life path cross Amsterdam’s authorities?

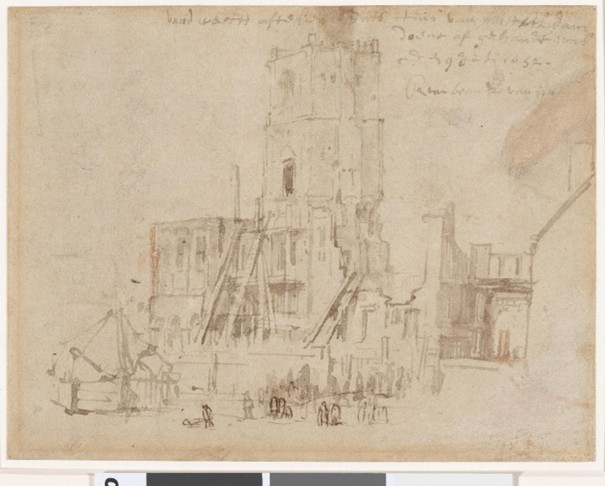

As his biographer Gary Schwartz (2006, p. 162) notes, it is perhaps exemplary of Rembrandt’s complex relationship with Amsterdam’s political elite that no painting of his hand depicts the glorious new city hall. Contemporaries called it the ‘Eighth Wonder of the World’, yet Rembrandt only sketched the smouldering ruins of its medieval predecessor the morning after it had burned down, 9 July 1652:

Rembrandt (1652), The Ruins of Amsterdam’s Old City Hall [Museum Het Rembrandthuis]

Rembrandt (1652), The Ruins of Amsterdam’s Old City Hall [Museum Het Rembrandthuis]

Already before the fire, Amsterdam’s burgomasters had ordered architect Jacob van Campen to design a new city hall reflecting their wealth, power, and dignity. After the fire, construction quickly started, and in 1655 the first floor was occupied by the most important urban courts and governmental institutions. Even if Rembrandt’s life events, therefore, brought him to temporary offices rather than in the rooms that can still be visited today, his life story is typical of the events and business that brought many of Amsterdam’s citizens to the current Palace on Dam Square.

Rembrandt, Titus, and the Orphan Chamber

Amsterdam’s Royal Palace includes a room called the ‘Orphan Chamber’. This was not intended to house the city’s orphans, but rather a legal-financial institution. In this room, five Orphan Masters ensured that no greedy hands of guardians or distant family members would harm the goods and possessions of children who had lost one or more of their parents. When Rembrandt’s wife Saskia Uylenburgh died in 1642, therefore, he was required to come before these commissioners to properly arrange the business of his son, Titus, who had not yet come of age.

In 1639, Rembrandt and Saskia had bought a large house, which included his studio (today, you can visit it as the Rembrandt House Museum). In May 1656, Rembrandt transferred this house to his son Titus. In the walk it is suggested that Rembrandt disadvantaged his creditors by this action. Some even argue that he committed fraud to the detriment of his creditors! Is that true? The document used in the correspondence with the Orphan Chamber does not use the term 'transfer’, but rather (in Dutch:) 'bewezen'. Even now, legal historians continue to be divided over almost all legal aspects of this case. To name a few points of contention:

- should Saskia’s family not have given consent to Rembrandt’s action with the Orphan Chamber?

- did Rembrandt act as 'owner', or only as Titus’ guardian, as a legal representative of his minor son?, and

- did Titus indeed become full owner of the house when he reached majority, when he was twenty-five-years-old?

Rembrandt (1655), Titus at his desk [Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, St 2. Bruikleen Stichting Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. Acquired with support of the Vereniging Rembrandt and 120 friends of the museum, photo: Studio Tromp]

Rembrandt (1655), Titus at his desk [Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, St 2. Bruikleen Stichting Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. Acquired with support of the Vereniging Rembrandt and 120 friends of the museum, photo: Studio Tromp]

Rembrandt’s Insolvency

Only a few weeks later, Rembrandt had to appear before another of Amsterdam’s subsidiary courts: the Desolate Boedelskamer or Chamber of Abandoned and Insolvent Estates. This Chamber, next to the former Chamber of Insurance and Average, is also located on the Palace’s first floor. Assisted by a secretary, bookkeeper, and several clerks, the five commissioners of this court supervised curators’ management of all insolvent estates in early modern Amsterdam. Unlike in other times and places, people who lost their credit and could not repay their debts like Rembrandt did not end up in a debtors’ prison, and neither were they confronted with shameful sanctions. Amsterdam’s commissioners sought to arbitrate an agreement between insolvents and the majority of their creditors, the composition or akkoord. If this was not feasible or efficient given the nature of the case, the respective insolvency procedure cessie van goede (boedelafstand) constituted an alternative that was used by most of Amsterdam’s insolvents. All their goods would be liquidated by the curators, often via public auctions. The proceeds received were collected by the court, and once the creditors had received their due, the former insolvent could attempt to rebuild their business.

In his application for cessie van goede Rembrandt had mentioned three causes for his financial problems:

- losses suffered in business,

- damages and losses at sea, and

- the threat of imprisonment. He probably feared the dungeon (de kerker) most!

Seven persons are named as creditors in Rembrandt’s application, including Burgomaster Cornelis Witsen. In the recently opened exhibition in the Royal Palace on Dam Square, focussed on the work of the great Artus Quellinus (‘Sculptor of Amsterdam’), a bust of mayor Witsen is on display in the Citizen’s Hall. Today, what is best known from Rembrandt’s insolvency is the inventory of over 300 items that was made in July 1656. It describes the paintings, furniture, and household goods belonging to Rembrandt, and was drawn up by Frans Bruijningh, the secretary of the Chamber of Abandoned and Insolvent Estates.

At the end of the day, however, insolvents like Rembrandt received a second chance in Amsterdam. They could once more contribute to the civic community and even receive prestigious government commissions. Rembrandt’s final involvement with the city hall clearly reflects that his insolvency must have been wrapped up in an orderly manner, even if the resulting painting was soon taken off the wall…

Rembrandt (1662), The Conspiracy of the Batavians under Claudius Civilis [Wikimedia Commons].

Rembrandt (1662), The Conspiracy of the Batavians under Claudius Civilis [Wikimedia Commons].

Rembrandt’s Painting Removed

Did you know that Rembrandt was asked to produce a painting for Amsterdam’s new city hall, that was eventually turned down for inclusion? One of the prominent stories represented in the building’s design is the story of the Batavians. They were mentioned by the Roman historian Tacitus as a valiant tribe, inhabiting part of what is now the river delta of the Netherlands. Claudius Civilis, leader of the Batavians, organised a revolt against oppressive Roman demands for taxes and army recruits. Even though the Romans eventually crushed this revolt, the Batavians received a negotiated peace that restored their former privileges. Of course, this story had great appeal for the Dutch, whose Republic was born out of a successful revolt against their Habsburg monarch. Rembrandt’s pupil Govert Flinck originally received the commission to produce twelve huge paintings depicting this story, intended to decorate the top of the gallery surrounding the central Citizens’ Hall.

When Flinck unexpectedly died in 1660, however, Amsterdam’s burgomasters asked Rembrandt, Jan Lievens, and Jacob Jordaens to complete the project. Whereas Flinck had depicted the Batavians in a more ‘civilized’ manner akin to the Romans, Rembrandt opted for a more exotic style. Lievens and Jordaens, however, stuck to a more classical interpretation. Schwartz (2006, p. 182) argues that once the paintings were in place, Rembrandt’s ‘semi-barbarian’ depiction of Civilis’ oath must have constituted too evident a discrepancy with the rest of the gallery. The painting was quickly removed, and Jurriaen Ovens was commissioned to complete Flinck’s unfinished canvas of the same subject. The central scene of Rembrandt’s work was eventually cut from the larger painting, ending up in the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm where it remains on display today.

Rembrandt’s most famous painting, The Night Watch, actually also hung in the city hall for a while. In 1715, the painting was relocated from the Kloveniersdoelen (the militia banquet hall for which it had originally been produced) to the city hall. The original painting was about 420 cm high, with a width of around 500 cm. While one would expect this large size to be no issue for the enormous city hall, The Night Watch was made fit for a smaller wall in the building. It was situated between two doors, which is why a strip has been cut off from all sides. This means that some parts of the original Night Watch have been lost. Amsterdam’s city hall has never been favourable to Rembrandt’s art!

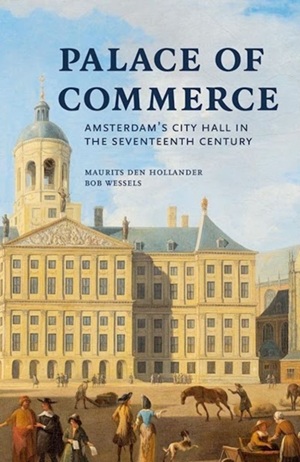

Palace of Commerce

Even if Amsterdam’s former city hall was refurbished as Royal Palace for Louis Napoleon Bonaparte in 1806, today as much as in the Dutch Golden Age its walls remain full of seventeenth-century masterpieces by Rembrandt’s colleagues and competitors. In our book, Palace of Commerce, you will find a selection of these works printed in full colour. You will get to know all about the City Council, the Treasury, and some of Amsterdam’s courts, as well as how the city hall was used and experienced by people in Rembrandt’s time. Would you like to learn more about how the iconography of each room carefully matched its original purpose? Order our book, and during your next visit of Amsterdam’s ‘wonder of the world’, you will know the hidden stories behind today’s Royal Palace!